Yann MingardThe Dark Side of the Earth

In Yann Mingard’s photograph, KrioRus, Alabuschewo bei Moskau, Russland (2010), the viewer’s gaze is drawn to a fibreglass receptacle surrounded by scaffolding. An expanse of old plastic sheeting is draped to the left of it in a rather makeshift fashion, softening the light that penetrates the metal hangar in which the vessel is contained. What the plastic is protecting is unclear – perhaps it is there to prevent the light from intruding. Filtered through the plastic, the milky backlight mutes the tones of the ochre vessel, which bears some similarity to a water heater. The image, which was taken in the Russian capital, is indicative of Yann Mingard’s whole approach: the artist sheds light on the dark places of our world, in a topographical and social-political sense.

This ‘shabby’ still life composed of rust, dust and grime, depicts one of the many places Mingard has visited in which life is preserved. Human bodies and brains are cyro-preserved here. For the sum of 36,000 dollars you can have your future corpse deposited here, but if you just want the service for your brain – no matter how impressive your IQ – a mere 12,000 dollars will ensure that it goes on living, albeit in another body. For all the aesthetic sophistication of the photograph, its subject matter automatically provokes a sense of unease, calling to mind the plot of Philip K. Dick’s novel UBIK (1969), in which those who have died remain in contact with their living relatives for quite some time after their death.

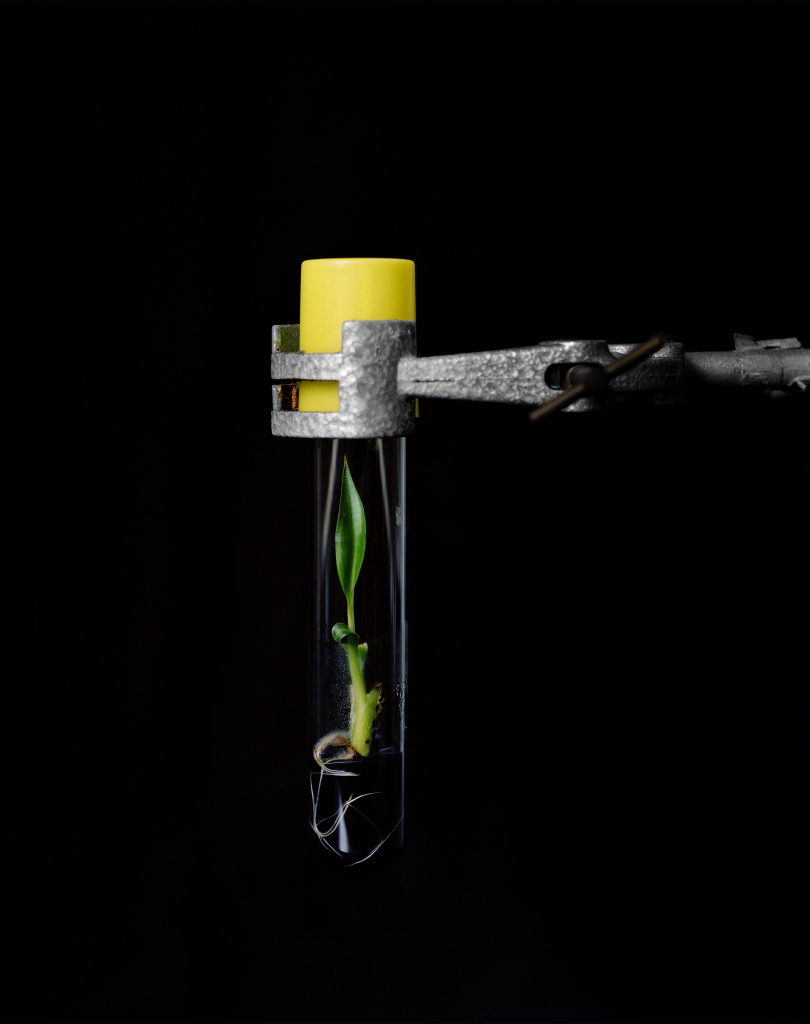

The entire Deposit series by the photographer, who was born in Lausanne in 1973, consists of the precise documentation of exactly the kind of thing that has long been the stuff of science fiction. From 2009 to 2013, Yann Mingard compiled an inventory of all companies that are actively collecting and preserving the DNA of humans, animals and plants. The very dark, colour photographs are made in, and depict, ‘animal-testing’ laboratories, large-scale agrochemical companies such as Syngenta, and sperm banks. These three sections have been supplemented by equally dark shots of places where the gold of cognitive capitalism – big data – is stockpiled and administered. Deposit was published in 2014 to coincide with the major exhibition at the Fotomuseum Winterthur. It made a big splash before moving on to the Museum of Photography (FOMU) in Antwerp and the Folkwangmuseum, Essen. In my view, it is one of the best photographic exhibitions to have been held in recent years.

The artist’s earlier work was also defined by a ‘dark’ gaze’. This time, it was trained on nature: areas of woodland and the very remotest forests. Having trained as a landscape gardener – Yann Mingard twice broke off his studies in art and photography in Geneva and Vevey to concentrate on this field – he examined the haunts of animals on the forest floor; where branches lie rotting, the undergrowth runs rampant and the line of the horizon is nowhere to be seen. His attention was keenly focussed on the terrain itself. The photographs were published in Yann Mingard: Repaires (2012). The book has long since sold out. Mingard’s first publication, which was imbued with his trademark ‘dark take’ on things, seized the attention of the photography world. Although many of his photographs were shot in dazzling snowy landscapes, East of a New Eden – which he created together with his friend Alban Kakulya, whom he met at an NGO in Nicaragua – sheds light on a world that tends to pass under the radar of wealthy Western Europe. The two friends travelled 1,600 kilometres along the eastern border of the European Union: from the Baltic to the Black Sea. The caption of each photograph is the exact geographical data for the location in which it was taken, as captured on their GPS device.

Yet the two photographers were not content with landscapes and portraits of people from these areas. They also wove into their book satellite imagery of the border regions and extracts of texts from various sources – not least a selection of statistics on the thousands of people who have died along the borders; those who have found their way into ‘rich’ Europe barred. These days Yann Mingard has distanced himself somewhat from his work for the Lausanne-based press and photo-agency Strates. Instead, he now trains the light of his photography on where he believes it should be shed – into the darkest depths. Thomas Seelig, co-director of the Fotomuseum Winterthur, believes that there are very few documentary photographers today who can come close to Mingard’s level of incisiveness.