Eija-Liisa AhtilaThe Cinematic Art of Eija-Liisa Ahtila

Eija-Liisa Ahtila’s fictional narratives, or ‘human dramas’ as she has called them, are drawn from her own observations, as well as from long periods of research. In complex multi-screen works, usually projected on multiple panels, she reveals the fragile psychic lives of her protagonists and the tenuous line separating fantasy from reality. Harshly poetic dialogue, technical control and understated performances result in haunting evocations of character and place, where psychotic and other extreme realities find a perfect embodiment in cinematic form. These vivid, fractured narratives depict the psychological impact of interpersonal conflict, and are attuned to the intricacies and ambiguities of human emotion and amorous discord.

As in most Ahtila works, past events intrude and press on the present. As such, grieving is well underway in Today (1996–97) – a work haunted by yesterday’s secret. In the first of three consecutive episodes, a teenage girl seems both disgusted and baffled at her father’s grief after the death of his own father, her grandfather. Over almost unwatchable images of the howling man in a foetal position on his bed, she explains: “Late last night, a car drove over his dad, who died instantly.” Vera, the principal character of the middle section, comments angrily on life and sexuality in the modern world. Is she the grandfather’s wife or the teenage girl of the first section mysteriously catapulted into the future? In the third part – where the father muses on being both a son and parent – we discover that the grandfather may well have deliberately orchestrated his own death.

In tense counterpoint, where at any given time one side seems to drive the action while the other side sketches a more atmospheric mood, the two screens which constitute Consolation Service (1999) ultimately coalesce in a spectacular failure of intimacy. It is early spring, and the landscape is still covered with snow. J-P and Anni, a couple whose depth of misery seems limitless, visit a marriage counsellor with their baby, while variously afflicted patients in the waiting room file invisibly into the therapist’s office and silently witness the proceedings. More spectral activity follows as J-P, the ‘absent’ husband of Anni’s anguish, performs an intriguing vanishing act in the third section of this complex and bitterly beautiful work.

Beginning with a premonitory anxiety dream in a winter storm in New York, and ending in prayer in Benin, West Africa, eleven months later, death is the protagonist of The Hour of Prayer (2005), a four-screen meditation on the death of a dog. ‘I spent a lot of time with my dog. In a way, we shared our senses and used them to think about our surroundings together.’ Such is the power of the narrator’s companionship with her beloved Luca-boy that she suffers a sensorial ‘amputation’ following his death. Interestingly, in an unrelated photo series, Dog Bites (1992–97), Ahtila stages a cruelly comical pantomime with a naked young woman in an array of knowing and empowered dog gestures – urinating, sniffing, stretching, etc. Here, the artist faces down the conventionally sexist and demeaning representation of women as animals – the ‘chicks’, ‘foxes’, and ‘bunnies’ of sexual invocation – while literalizing the ‘bitch’.

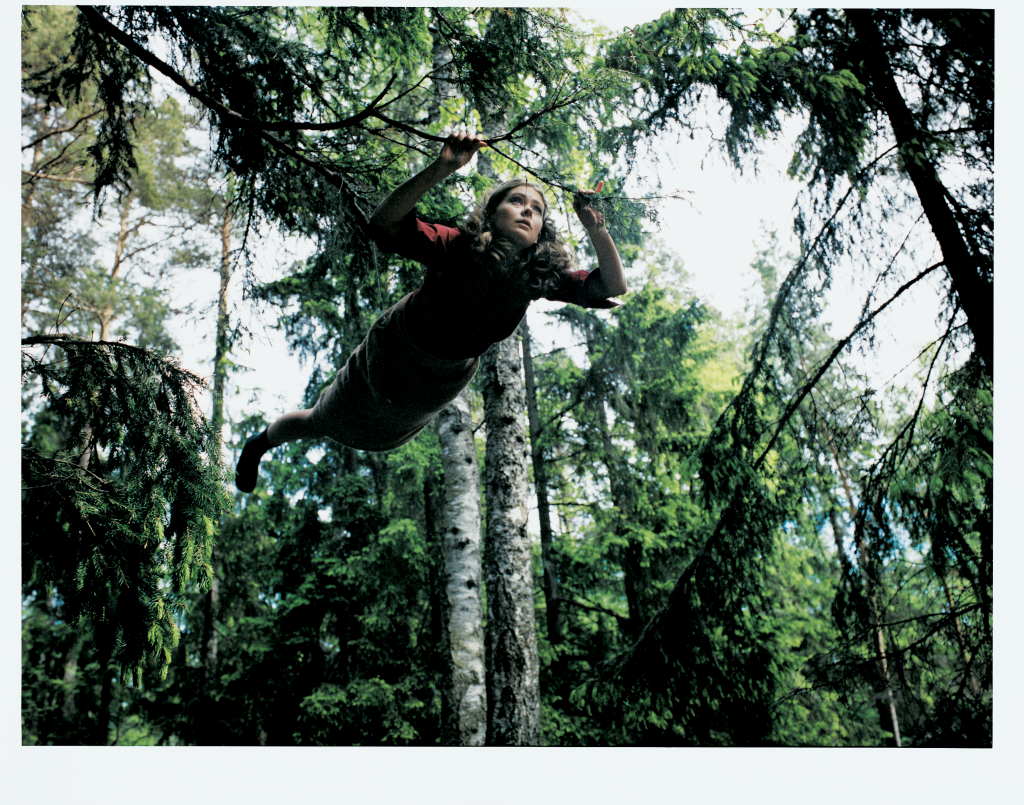

Ahtila’s experimentation with narrative and multiple perspectives may suggest madness as a paradigm of all mentation. Indeed, simple causality has been entirely jettisoned in favour of an elliptical, warped time of overlap, simultaneity, hallucination and grieving. The Present (2001), a depiction of women who have developed a psychosis, is shown in five short, looped episodes on five separate monitors. Only two episodes are playing at any given time, while the other screens display red, green or blue, the RGB colour model, which constitutes the palette of analogue TV and cinema images. Amid glorious colour camerawork, the artist deliberately invokes the ontology of all images and representations. One woman is seen crawling across a bridge, another lies down in a puddle; one bites her hand repeatedly, another hears sounds detached from their objects of origin. This latter episode is fully fleshed out in the majestic installation The House (2002), a haunting three-screen film in which a woman quietly goes insane in an old Finnish seaside cottage. “Outside, a new order arose, one that is present everywhere,” she states ominously within a mounting confusion of sounds heard from impossibly far away, which she experiences in an untenable simultaneity with her own thoughts.

The plot of Where Is Where? (2008) revolves around two Algerian boys who murder a French playmate in an act of revenge against the perceived European hatred of Arabs – a confused, angry, and tragic reaction to French brutality during the Algerian war of independence in the 1950s. The work also centres on a Finnish poet and her efforts to untangle morally this real-life incident.

This monumental, six-screen, fifty-three-minute epic begins with an animated film sequence, but the main drama is played out on four large synchronized screen projections. Thematically, politics and religion mingle with the creative process, and this mingling finds a perfect embodiment in the poet, who struggles with both words and her preoccupation with the existential ramifications of the Algerian War. Where Is Where? is Ahtila’s latest and perhaps most ambitious work. A knight’s move for the artist who here, for the first time, principally considers the emotional trauma suffered by war’s civilian victims. This turn to historical and political considerations augments an already important body of work concerned with wide-ranging spiritual and existential matters.