David Bennett and Neil PereiraIlford IG1

David Bennett and Neil Pereira in conversation.

Neil Pereira (NP): It was strange that we’d lived in Ilford most of our lives but had only known each other a sixth of the time. When we first met, I was struck at how your life was immersed in photography, and that ignited my passion for it; I had just started designing Art Review, but creatively it was not enough.

David Bennett (DB): For me, it was knowing like-minded people existed after graduating from Farnham. I felt claustrophobic living back in Ilford, but then realising you and Nick (Nicholas Parsons, the third member of the collective) had a similar way of thinking, it became positive.

NP: It just seemed inevitable that we should somehow document the town, especially as it’s the birthplace of the black-and-white film company. The idea of three ‘Ilfordians’ photographing Ilford, using nothing but Ilford film, seemed potent. I remember reading the name on a roll of Ilford HP5 at Newham College; I never really associated it with where I was from, as the livery portrayed a slick multinational company. The images on their photographic paper boxes were these dramatic red-filtered shots of St Paul’s Cathedral at dusk; it just seemed incongruous with where we lived, and I wanted to show that they were in fact related.

DB: We were worried about showing our project to Ilford Imaging in case they used the idea, and it turns out they don’t even like it.

NP: It was quite demoralising when we sent a letter to them along with a selection of work, and they sent it straight back with a generic response on how they already did enough for ‘charity’.

DB: It’s bizarre that there’s no testament to the company’s existence: no stone, no plaque, nothing at all. Whereas Kodak has Eastman House (George Eastman, founder of Eastman Kodak), which is a stately home with a vast Kodak photographic collection, with Ilford it’s as if the company never existed. The factory site is now a Sainsbury’s supermarket.

NP: The corner house on Park Avenue where Alfred Harman started the business isn’t marked at all, it’s just another pub. Ilford itself is just another small, Greater London town, with a pedestrianised high street and a plastic shopping centre. After feeling inspired by the first roll of film, I realised how arduous the project was. The subject matter just seemed banal.

DB: But I think in 30 years’ time, people will look differently at the pictures. When you look at the Stephen Shore images of Amarillo in Texas, he just photographed normal buildings and shopping malls; at the time he may have thought the same, but now the whole sense of place is of great interest. Maybe that will be the case with these. I found it difficult at the beginning as well. When I went back intentionally to shoot, I would just spend the whole day walking around, getting depressed. It was only when I went back to visit my mum that I ended up making images that I thought were good enough.

NP: I think because Ilford seemed so bereft of interest, it made us dig out the creativity inside us. I really had to grapple with it, and that made me extremely discerning. There is no middle ground, they look either amazing or just bland. Like those Richard Billingham photographs of his home town, they tread the line between being sublime or plain boring.

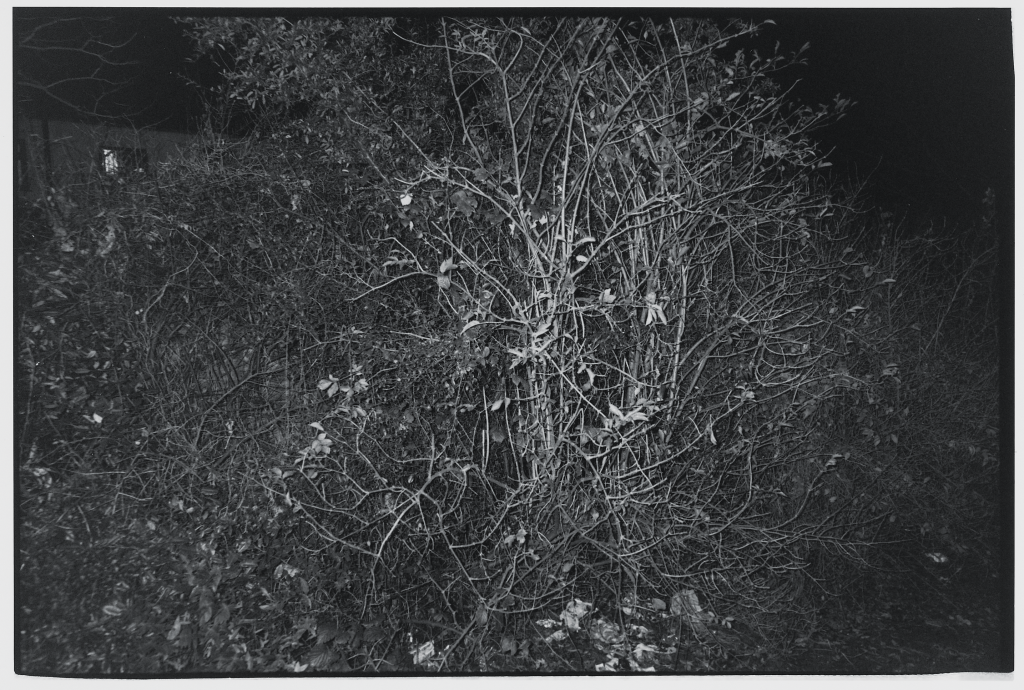

DB: Those Joel Sternfeld photographs of a derelict New York railroad track were a good reference point.

NP: Just incidental photos of a dilapidated railroad completely overgrown with weeds and flowers. It was that challenge of transforming the ordinary into something awe-inspiring. I think that’s a good creative quality yardstick, and rewarding when it’s achieved. Do you remember when we originally gave ourselves designated areas?

DB: I was quite happy with the pictures I took of Fairheads (a ’70s-style department store), but it seemed like a snippet of something bigger. It felt as though the project should be more substantial, more like 200 images to be made into a book. And then Nick decided not to carry on; he was such an integral part of the equation, but he just lost interest, got demoralised and gave up photography.

NP: It’s sad because he’s a highly talented photographer. It started off being a document of Ilford but it’s turned into a testament of the place, the company and our friendship.

DB: The project took a turning point for me after I was attacked taking photographs of a neighbouring street. These were, for a long time, my streets, my neighbourhood, my existence. The whole sense of belonging and nostalgia was taken after this incident, and I no longer feel the same association as I had before. Has it developed into something else for you?

NP: I find I can transfer all the ideas we’ve developed with the Ilford project into other projects that don’t have the same restrictions, especially using colour. You see things in a different light when you work in black-and-white. It’s only recently that I’ve realised that light is the essence of photography; without light, you have no photograph.

DB: I was looking at the work of Willie Doherty. He did a fantastic series of photographs in Berlin where the images are almost entirely black, but you have these bits of interior light coming through from the buildings.

NP: It’s all about different qualities of light. I start seeing how things are going to look in black-and-white as opposed to colour, and how flash is more forgiving with it but becomes incredibly critical for colour, and so you start having a foresight when you look through the lens.

DB: After I did the bush shot I was thinking of shooting a series at night with flash; seeing things how I never see them in daylight, where the subject is often camouflaged. When lit by flash I can see the structure of something else.

NP: It’s quite odd that Ilford has become such a source of information.

DB: It’s a vital point in both our work. Not just the Ilford project, but any other work, the way we think and see things, it really does stem from that time growing up there.