Rotimi Fani-KayodeCommunion

At the centre of the Isenheim Altarpiece 1512–1516 is a beautifully grotesque representation of the crucifixion. Painted for a hospital chapel at the Monastery of St Anthony (in Germany, now modern France) this panel depicts Christ afflicted with the illness the Antonine monks devoted themselves to treat, the then incurable and fatal skin disease known as St Anthony’s Fire. Sufferers experienced painful skin lesions, severe muscle cramps, gangrene in extremities and hallucinations, on their way to certain death.

The altarpiece was intended to act as a psychological passage allowing patients to identify with Christ in such a way that they would accept the story of redemption, transformation and resurrection that was narrated through the visual codes of his body. Though (like them) afflicted and near death in the first panel, Christ transcends the boundaries of the body in the resurrection panel. In the process, his material body moves from being lit in death to becoming light in its discarnate form.

In works such as Every Moment Counts (1989), Rotimi Fani-Kayode allows the image to play a similar role to that of Grünewald’s, as interface in a formal and epic discourse of being, one which is, unlike the altarpiece, right here on earth.

In the photograph, one feels the body warmth of the figures trapped beneath the soft volumes of the red velvet brocade. The men’s skins burn orange in the light. As they turn towards its source, the triangular formal unit that unites them erupts in the sorrow of inevitability. Moving through the image, points of light reveal tension and instability in the composition, from the hands and furrowed brow of John the Beloved, to Christ’s bright, red, glassy eyes.

Like Grünewald’s crucified Christ, these men take shape against a literally black background, allowing light — as form and language — to mediate between what is known in the cultural referent and what is desired in Fani-Kayode’s contemporary turn. As a result, the image simultaneously evinces passion for life and death, continuity and change, the present, past and future, without ambivalence. Instead, one senses the exact opposite: an urgent prophetic vision. Fani-Kayode sees the possibility of a different end to this story: a time when we would have the power to rewrite and redirect what we once imagined was inevitable and inhabit the impossible.

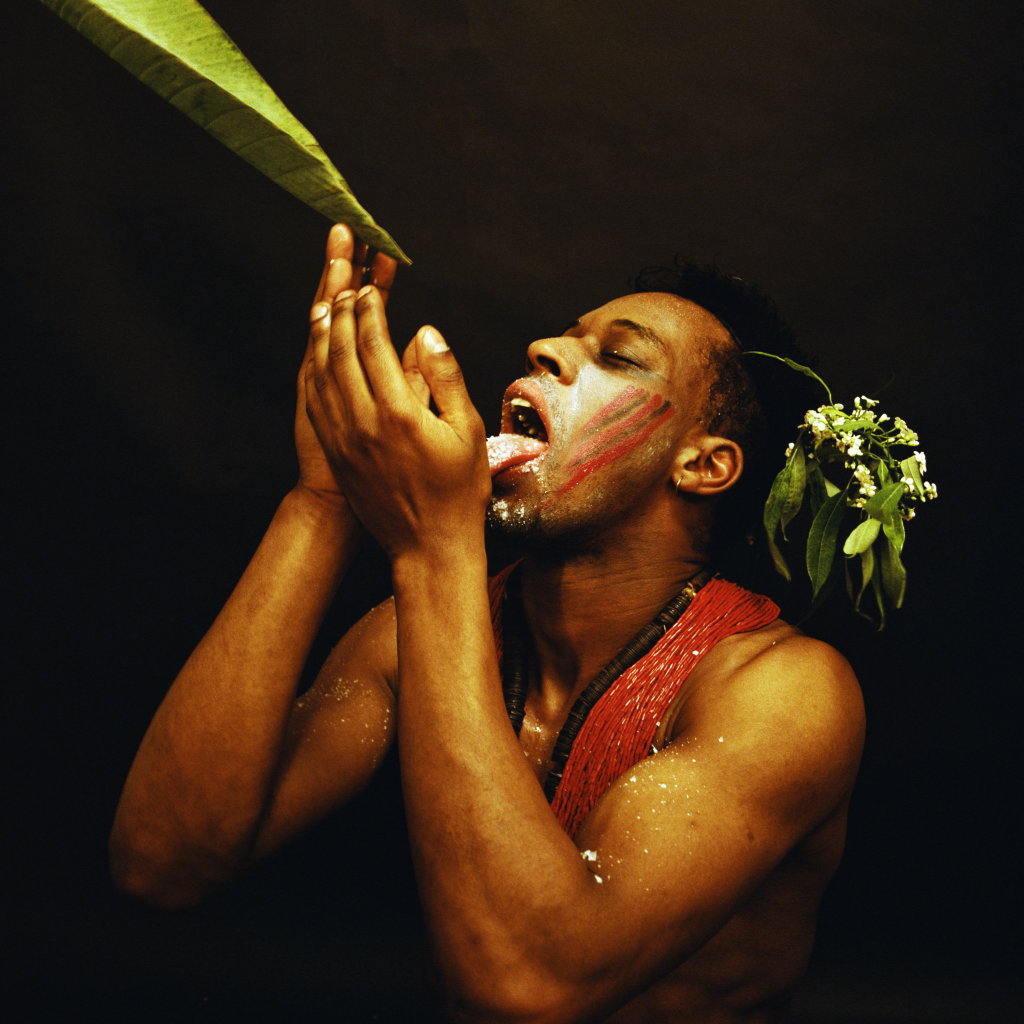

The work Sonponnoi (1987) holds within its form a similar imperative that is as certain as a Doudou N’Diaye Rose drumbeat. Created during a time of ignorance, hysteria and deep-seated fear towards people with AIDS, this image holds within it a level of self-possession and confidence that is almost surreal. The light reveals a black male sitting with his legs open, near the surface of the composition, reducing the formal distance between the image and the viewer. His hands hold three fully lit white candles just off centre, shielding his crotch from view. His body is covered in pink, black and white dots and occasional stripes that reverberate with the scars of smallpox and Kaposi sarcoma, but also the West African fraternal Leopard Society’s ceremonial dress. Formally the spots become prismatic in the light, appearing to be simultaneously glowing on the surface of his skin, levitating above his body and emanating as light from his body. The figure wears a thin gold chain and a necklace made from disks of seeds or coconut shell. His navel is shaped like an all-seeing eye.

For a moment let’s recall Man Ray’s image of Kiki de Montparnasse’s head next to the black African mask from around 1926 or, even better, the image of his Guadeloupean muse and lover Adrienne “Ady” Fidelin next to African sculptures in the late 1930s. These works picture modern concerns of duality and difference, the primitive body and the fetish, in a manner that resists the interpolation of ideologies, reinforces the fixity of otherness, and supports a specific architecture of engagement, defined as culture and read as normative. In these images, bodies and objects are subject to historical and aesthetic frames that invite curiosity, while refusing interface.

Fani-Kayode’s oeuvre articulates the necessity for the beautiful disfigurement of philosophies of visuality and being that underpin modern aesthetics and culture. From the still power of Sonponnoi and the emotional tension of Every Moment Counts to the pared down formalism of his own Ibeji twin images, he evinces a postmodern baroque aesthetic that insists on complexity and authorship. Fani- Kayode willed this future present, envisioning black male bodies, not as fetish, freak or a source of fear, but flesh.