Advertising Space

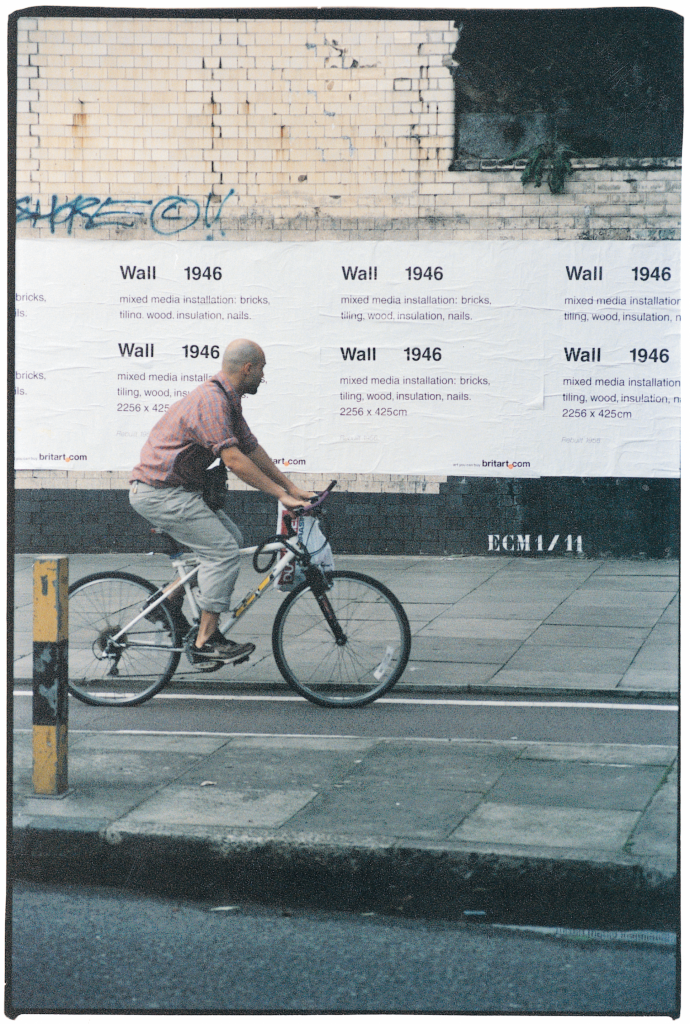

Ever since the explosion of posters in Paris in the late 19th Century, the streets have become a battleground for brands. It can be seen in the photographs of Edmonds, Marville and, later, Atget which depict the streets empty but for the visual clamour of posters; advertising everything from biscuits to florists, theatres to medicine. They documented a new environment: one dedicated to communicating with the public at all times through the medium of the printed sheet. Poster sites also became a focus for ‘civic minded’ politicians and commentators on modern life. Maurice Talemeyr, in his article The Age of the Poster (1896), saw poster advertising as reflecting the ephemerality of the modern world — no sooner was one advertisement up than the next day, it was obliterated with another competing product. However, this point of view neglects to acknowledge the poster as an historical artefact: a tangible reminder of our past, applied to the streets of our towns and cities. You can, quite literally, peel back the layers of time at a poster site, and see the faded evidence of events and products that have been before.

Fernand Leger saw the poster as symbolic of an exhilarating modern age — a riot of colour and type amongst the drab city streets and, in its own way, an antibourgeois symbol. For, despite the posters’ attempt at persuading the masses to buy consumer goods, its very presence on the street, in all its gaudy splendour, is an affront to the banal. Other artists too, were inspired by this commercial medium, including Kurt Schwitters. Although he concentrated on small-scale advertising ephemera to create his work, I can’t help feeling that the city walls around me are like one, huge Schwitters collage — a celebration of modern life in all its perfect chaos.

In an attempt to control this ‘chaos’, one London council has invoked the Anti-Social Behaviour Bill against advertisers who use flyposters as a medium. The legislation, more commonly used against vandals, prostitutes and drug dealers, is an extreme measure but emphasises the continuing impact of the poster.

Next Level (NL) spoke to Addi Merrill (AM), Communications Director of the ambient media agency Diabolical Liberties, who recently published Your Space or Mine?‚ an examination of the role of art on city streets, to hear her views on posters and communication:

NL: Mass poster campaigns have been part of the cityscape for nearly 150 years. Do you think posters will exist in the city of the future?

AM: I’d like to think that people will always use posters as part of their spontaneous communications in the city. The urban landscape is constantly evolving, so where and how fly posters appear may well change, moving onto authorised sites rather than appearing randomly on city walls. There will always be cultural events and creative people using posters within their locality. The only reason this would end is due to draconian changes in the law. It would be a very sad situation if our government allows the criminalisation of cultural advertising, and it is subsequently banned with no alternative solution accepted.

NL: Will fly posters remain in the same form, or are there new developments and possibilities for street advertising?

AM: As I mentioned above, the format will no doubt move forward as a city develops, and the biggest change will hopefully be a regulated system for giving street posters legitimate space through community focused schemes. Diabolical Liberties supports these schemes because a minimum of 40% of the space is allocated specifically for local posters from the arts, charities and community groups at vastly subsidised rates. That’s good for our grassroots culture and means the community have a place to advertise their events at a really affordable rate. Street advertising can take all kinds of formats, as an agency working in ambient communications we’re constantly coming up with new ideas using unconventional media to access a specific audience. We’ve people out on the streets all the time, seeding ambient messages in all kinds of intriguing styles.

NL: Do you see the use of the flyposter as an extension of the advertising world’s attempt to appropriate street culture for its own ends?

AM: Street culture, alongside youth culture, is the foundation from which nearly all modern trends, creative direction and new fashion thinking are influenced. It makes sense that the advertising industry naturally draws from this free and fast changing creative pool in order to find inspiration. Street posters have always been a tool of cultural advertising and, therefore, those brands who have an interest in young people and their culture have naturally adopted the best form of outdoor advertising to reach them. Nearly all street posters advertise either events, music, fashion, arts or brands that appeal to this distinct audience.

NL: As the development of the ‘global village’ continues, do you feel that the flyposter is even more relevant to society— through its ability to appeal to both the immediate community (with adverts for local gigs etc.) and the broader market (adverts for big brands)?

AM: I’m not sure I really believe in the concept of a ‘global village’. It has undertones of homogenisation and one world with one creative style. There is no doubt that one of the challenges of modern cities is to ensure that a sense of connection to local communities by the people who live there continues to exist. Street posters support this concept, effectively linking disenfranchised city folk to their local area via advertising events, arts and notices in the immediate vicinity.