Robert DaviesOne

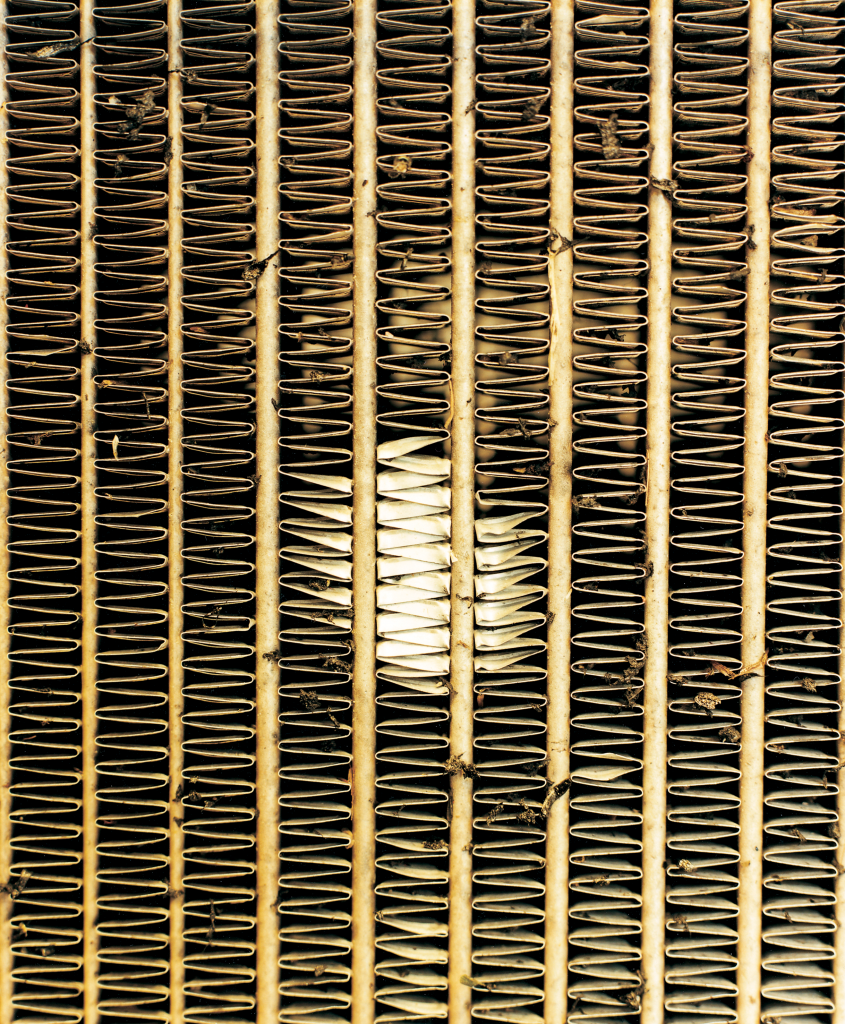

ONE is a unique photographic collaboration, a series of exquisite photographic works by Robert Davies (RD), which were exhibited at the Blue Gallery in London in 2005. Davies’ photographs offer a radical alternative to the sports and lifestyle photography so closely associated with Formula One and the exhibition laid bare the Formula One obsession with, and worship of ‘detail’ in a manner that was both aesthetic and dispassionate, poetic and yet clinical. For B.A.R Honda, the sponsor and partner of the project, the experiment was a revelation of what was previously unseen: order and precision, the choreography and the obsession with ever-smaller measures of time. One photograph, in particular, seemed to sum up the ordered world observed by Robert Davies – a huge close up of a Formula One hive-like car radiator, honeycomb-patterned and coated in gold.

The set of photographs are above all the story of a collaboration between an artist and an area of sporting endeavour that contrives also to be a science. In early 2004, as a result of one of those unlikely coincidences, I was introduced to David Richards, then chairman of B.A.R Honda, who proved to be a man with a passion for motorsport, design and more recently, contemporary art. What was interesting from my point of view was his appreciation of ‘art in the detail’, an interest which he extended to his business, from the spotless, clinical, architecture of the Formula One factory to the precise, cold, sculptural beauty of its mechanical components. Richards had some experience of working with artists in the past – Julian Opie for example, had received a commission to produce a series of portraits of B.A.R Honda drivers, similar in style to his earlier Blur portraits – but these had proved to be largely a wasted opportunity, with little mutual, long term impact between the artist and the high profile but cloistered world of Formula One. My criticism of the superficiality of the previous project and the assertion that artists needed to be allowed into the very heart of an organisation like B.A.R Honda, led indirectly to a challenge to David Richards and the seeds of this rather unique arts collaboration. Details were worked out through a series of meetings and phone calls over six months which ascertained the level of access to be offered to the artist – unprecedented access indeed in sporting terms, for the sport is notoriously closed to outsiders and jealous of its technical prerogatives. This included full visiting rights to B.A.R Honda’s testing activities in Jerez, Spain, a place trackside at the French Grand Prix in Magny-Cours, an invitation to the team’s Operations Centre in Brackley, Northamptonshire, and a place at various Grand Prix events in Regents Street, London.

In return for this open door policy, it was agreed that the artist would produce a body of work without censorship or interference. Obviously a critical element in the process was finding an artist with the natural empathy and abilities to discern what sportswriter Richard Williams later defined as the “poetic dimension” within the “leading edge science”.

We were fortunate to find Robert Davies through the FIFA 100 exhibition at the Royal Academy, for his unusual images of our national sport – pixelated and blurred, shot straight from electric, coloured, videos – gave the photographs of sporting icons an otherworldly and disturbing aura. This exhibition, plus a remarkable body of work called Epiphany, marked him out as someone who would not be distracted by the mountains of over branded, primary coloured, glamour photography that already existed in Formula One.

It was this interest in the ‘edge’ of vision that made Robert Davies the right choice to become the critical observer of the tight-knit, carefully choreographed family of individuals driving the fortunes of the B.A.R Honda team. Davies’ interest in the absurd, the distraction of ‘irrelevant’ detail and his need to explain the importance of a positioning mark on the floor, a colour coded valve or the right grade of foam in the headrest rendered him almost invisible within a team where every individual had one repetitive, but essential role to fulfil.

After the project Davies described the revelation that four hundred people, from the car’s designers to the catering staff, drivers, mechanics and engineers were uniquely responsible for the success or failure of the team. What Davies realised early on during the commission was the importance of detail, that “everyone is doing a piece of work that is trying to make the car one hundredth of a second faster”. Ironically his role as ‘outsider’ eventually helped Davies win the (often uncomprehending) co-operation of the trackside team.

The success of ONE reinforced my view that the artist should be at the centre of things, at the front of the queue as it were, using the newest technology, working in collaboration with manufacturers and scientists, doctors and philosophers. It also confirmed Futurecity’s role as facilitator and interpreter for different (and at first sight seemingly incompatible) worlds.

JW: I should begin by talking about the unprecedented access you were given by the B.A.R Honda Formula One team.

RD: I was very lucky to be part of this commission. Formula One is a strictly controlled environment so to have the opportunity to spend so much time with the team, whether they were testing, at a Grand Prix or at the factory made the whole project that much easier, and hopefully more interesting. I was given the time and space to consider this technology-driven sport and was able to translate that experience into the visual language of these photographs.

JW: Had you had any experience of Formula One before?

RD: I come from quite a big family and my brothers and dad were always talking about cars and motor racing. We used to go to Silverstone in the 1970’s when it was easier to get close to the cars and drivers. We used to watch Barry Sheene as well and he stayed in a caravan at the track on race weekends. We were pretty casual observers.

JW: The world of Formula One is very familiar to us. As an artist, you were given the opportunity to portray it in a fresh light. What were the key differences?

RD: Formula One is one of the most popular sports in the world. The money and glamour attached to it are celebrated in magazines and newspapers to a hugely saturated degree. Photographers cover every aspect of Grand Prix, taking pictures of the cars, their famous drivers, the power brokers and the glamorous hangers-on who follow the sport. I think there are 400 accredited Formula One photographers all working for different publications in different countries. It appears they all use similar equipment – 35mm cameras with very long lenses, in an effort to capture every facet of Grand Prix life. They are almost bound to duplicate one another so the pressure on them must be suffocating. I was fortunate. I was given the chance to make work that didn’t revolve around personalities or news. I observed the workings of the team very closely, with time and the organisation on my side. I was able to use a medium format camera and a tripod as I carefully selected the things I wanted to photograph. You have to be very deliberate when you use a studio camera so a working garage isn’t the most conducive place to operate. All I needed to do was agree when it would be least disruptive to the mechanics. Sometimes I could just slide in when they were concentrating on other sections of the chassis and other times they left the car for me, in the stripped down state I had requested, and let me get on with it.

JW: What impact did this have on the work you produced?

RD: After spending time with the team in Jerez in southern Spain, I had a very different understanding of Formula One. Due to copyright restrictions, I was unable to take any photographs or film any footage. Whilst this was frustrating it did give me time to concentrate on the possibilities for the project. As an artist sometimes it can be invigorating, a real challenge, to have restrictions placed upon you. It forces you to think more creatively. The most striking thing about Formula One is the number of people involved in a Grand Prix team. I think B.A.R Honda has in the region of 400 employees and every single one of them is trying to facilitate the objective of maximising the car’s speed around a track. Be they designers, engineers, aerodynamicists, mechanics or drivers, they are all dealing with the minutiae of their field in an effort to improve the performance of the car. If you try to visualise this attention to detail it should give you an understanding of my pictures. There are so many crucial parts to the efficient working of a Grand Prix car. The power of the engine, the strength and adaptability of the chassis, the nature of the handling or the grip of the tyres. All these things must be working to their optimum if the team is to be successful. For the French Grand Prix at Magny-Cours, for example, less than ten one hundredths separated third from sixth on the grid after qualifying. The differences are scarcely measurable. So I decided to focus my camera’s attention on the detail of all the visible surfaces. By attaching extension rings to my camera I was able to go very close to all the materials, photographing areas as small as the palm of my hand. And it started to yield some interesting results. I photographed brand new tyres, those that had been used for an ‘out’ lap, qualifying tyres and race tyres, all showing different amounts of deterioration, but each describing a completely new surface. The level of detail and the changing nature of the rubber made them look like satellite photographs. I photographed the oil and water radiators, one a beautifully symmetrical piece of engineering whose patterns look more like a contemporary ‘process’ painting, the other a dirty and damaged piece of equipment whose function defines its form. I also photographed the protective foam of the detachable headrest in the cockpit. It is designed to protect the driver’s head and at first viewing is a regular piece of equipment. But on closer analysis it takes on other characteristics, appearing to be a picture of an expanse of space, not a minute detail. However, like everything else on a Formula One car its form is only decided by its function. Whether consciously or subconsciously, the designers and engineers are making equipment that has one reason for being (to be effective) but happen to be beautiful and compelling at the same time.

JW: And this red and black circular pattern?

RD: The rain light. This is one of the most striking pictures. For safety reasons, Formula One had to develop rain lights due to the huge amount of spray thrown up by modern Grand Prix cars. A single LED light is fitted to all cars beneath the rear wing. On close inspection, this is a stunning detail. The brightly lit red lenses are like atoms or nuclei, part of a greater organism. But by removing their context we are left with the things themselves. On seeing me photograph the rain light the chief mechanic at B.A.R Honda, Alastair Gibson, asked if he could have a look through the viewfinder of my camera. And I think he was pleasantly surprised. Something he had seen every day of his working life was yielding a different response simply by changing the context. And in essence this is the job of an artist, to look at our culture and surroundings and to reinterpret them for today’s audience. Our understanding of this increasingly complex visual language is being extended all of the time and my work is seeking to add to this.

JW: I wanted to ask you about context and the relation of this work to your existing practice.

RD: The camera is a tool, like a pencil of a brush. Photography isn’t one-dimensional and is being used in many ways in contemporary art: to depict the epic; to describe the world; to reveal and conceal the truth and as an abstract medium where the process denotes the form. I try to be flexible in my use of photography. These photographs, and the context in which they are shown, use photography in its most prosaic yet descriptive way. They explain the effectiveness of function through form.